operator. For that reason, there is of course no train-order signal at

the depot.

Moreover, passenger trains, even the mail train, would not ordi-

narily stop there (I might consider occasional flag stops). In daylight

hours, there were just two pas-

senger trains: the Daylight in

both directions, and the mail

train, nos. 71 and 72, in both

directions.

For freight operations, SP prac-

tice on most divisions was to

operate through freights, that

is, freights which ran from divi-

sion point to division point,

without any intermediate

switching. These were usually

scheduled trains (these are the

trains you see in [4]), with addi-

tional sections, and sometimes

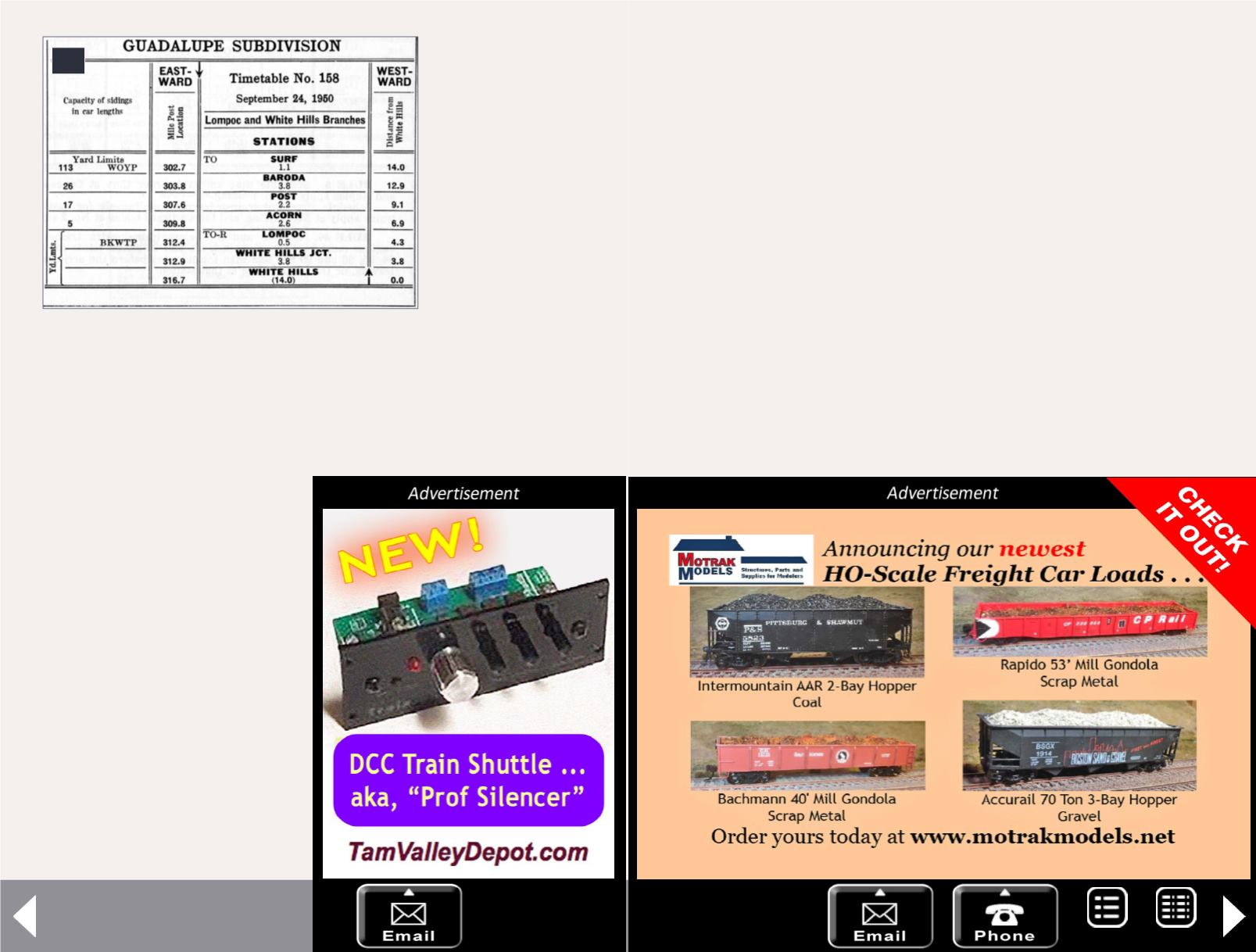

11. The pro-

totype time-

table for the

Lompoc and

White Hills

Branches,

from Timetable

No. 158 of

1950.

11

extra trains, as needed. I duplicate this on my main line by operat-

ing freights which simply pass by Shumala in both directions.

The mainline schedule therefore shows, in effect, the freight and

passenger trains which pass Shumala without interacting. This

makes the schedule in my timetable really only a guideline to a

lineup of the trains that will appear on the main line.

Let me digress to explain that a lineup or sequence of events is a

simple way to conduct operations. You would simply write a list of

the trains that will run, in time order. Maybe it would say some-

thing like, “run the hotshot freight westward; run the mail train

eastward; switch local industries in Epsilon and then run the local

freight as far as Delta, do needed switching en route, return.” This

avoids time pressure, because each train movement only takes

place once the previous one has been completed. In my case, as

described above, the layout arrangement is such that a timetable

really provides only a sequence of trains.

MRH-Oct 2014